Vietnam’s Rice Caught Between Two Models of Development

Background

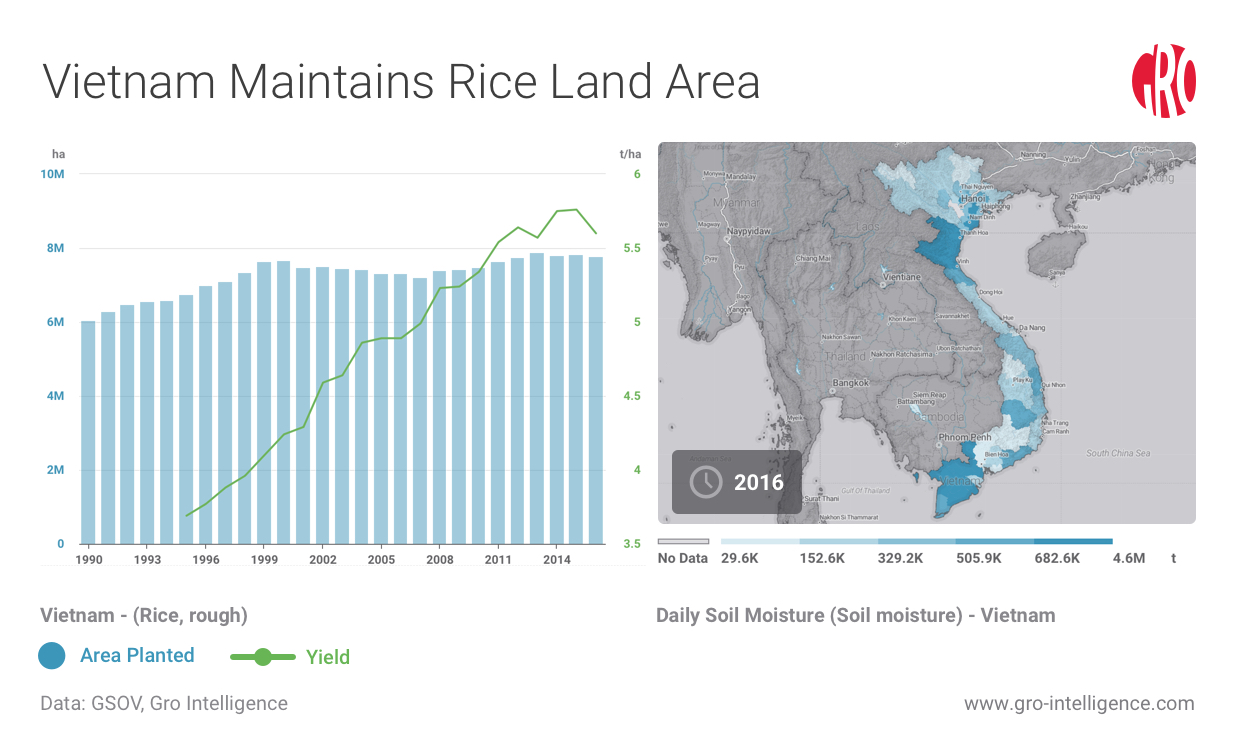

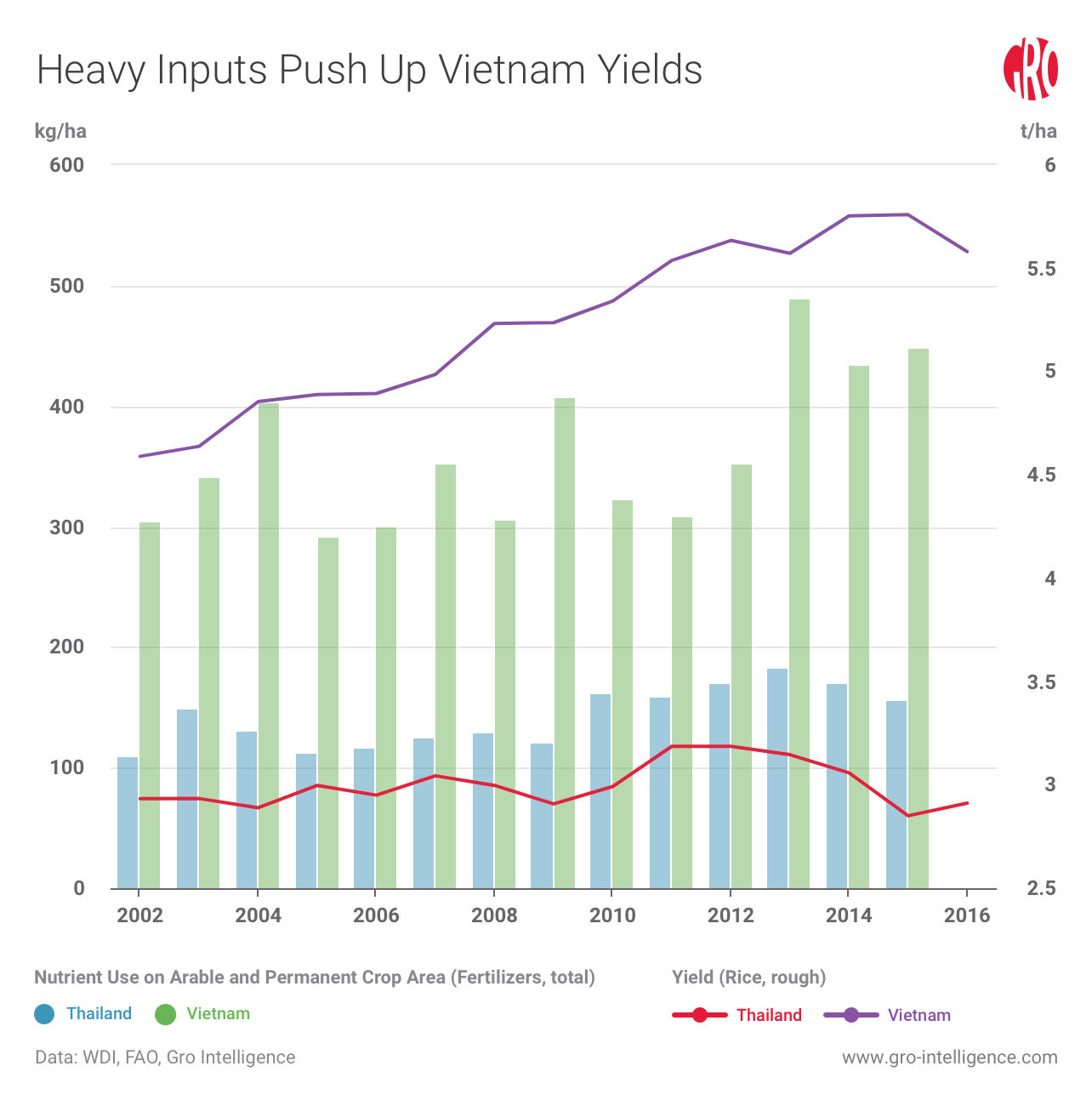

Rice production is critical to Vietnam’s agricultural industry, contributing 30 percent to the country’s total agricultural production value. Planted area of rice peaked in 2013 at 7.9 million hectares, an increase from a decade low of 7.2 million hectares in 2007. Yields have remained high at a 10 year average (2006-2016) of 5.41 tonnes per hectare. Vietnam’s yield greatly surpasses that of Thailand, another large rice producer in the region, with a 10 year average (2006-2016) yield of only 3.02 tonnes per hectare.

Most of Vietnam’s production occurs in either the southern Mekong Delta or in provinces like Thanh Hóa in the north. Kiên Giang, a province located in the Mekong Delta, is known for its rice production, producing 4.16 million tonnes of rice in 2016. Vietnam’s 10 year average (2006-2016) rice land area is relatively high compared to other rice-producing countries in southeast Asia at around 7.60 million hectares. Vietnamese rice land area is second only to Thailand with a 10 year average (2006-2016) of 10.84 million hectares.

Rice Land Preservation Policy

In 2012, the Vietnamese government enacted Decree No. 42/2012/ND-CP, which was replaced by Decree No. 35/2015/ND-CP in 2015. The decree provides 500,000 Vietnamese Dong (VND) per hectare per year to farmers directly producing rice, approximately $22.00 (USD). The policy aims to improve farmer incomes, maintain total area of land devoted to rice production, and increase rice exports. Implementation of the policy in 2012 had a positive effect on total production area, which increased from 7.76 million hectares in 2010 to 7.9 million hectares in 2013.

However, government restrictions on land use prevent smallholder farmers from profiting by using the land for other agricultural uses. According to Decree 69, Articles 6.1 and 10.1, rice farmers must acquire permission from local authorities before diversifying the crops they grow. Decrees 69 and 35 have contradictory goals, as keeping farmland in rice production will not necessarily improve farmer incomes. Instead, farmers should have the flexibility to choose the most appropriate crops for their parcels of land without governmental interference.

Environmental Loss Support

Decree No. 35/2015/ND-CP also establishes government support for farmers who suffer from crop losses. In 2017, floods in the Mekong Delta destroyed nearly 8,000 hectares of rice land, completely wiping out the summer-autumn crop. Fifty to seventy percent of farmers’ costs associated with crop losses due to disease and natural disasters are covered. The decree also covers 70 percent of the cost of acquiring new rice lands for production. And once land is acquired, the government will cover 100 percent of the rice seeds to be planted in the first year of production.

These types of policies benefit smallholders the most, and in an environment where it is difficult for farmers to acquire capital, government protection from extreme weather events like flooding is critical for farmer retention of crop incomes.

Crop Intensification

The Vietnamese government has promoted crop intensification to increase rice exports. However, this practice comes at a price. At 297 kilograms per hectare, Vietnam has the highest fertilizer use density among countries in the region. Other southeast Asian countries apply an average of 156 kilograms per hectare of rice area. This explains the relatively high rice yield in Vietnam of 5.6 tonnes per hectare in 2016, compared to Thailand at only 2.92 tonnes. Economic pressure on smallholders has them increasingly choosing to forego crop rotation in order to maximize annual production. Planting rice two to three times per year on the same parcel of land increases the likelihood of pests and disease

The System of Rice Intensification (SRI), a practice developed in Madagascar in the 1980s, has been promoted by both environmental protection advocates and proponents of rice intensification as a means for economic growth. This agronomic intervention is specific to smallholder-led agricultural systems, and thus well suited for Vietnam, where the average plot size of rice produced in the country is 0.5 hectares. SRI encourages the planting of young seedlings at a seeding rate of five to seven kilograms per hectare and when seeds are eight to 12 days old, versus planting seeds when they are 21 to 40 days old at a conventional seeding rate of 50 to 75 kilograms per hectare. SRI also advocates for increasing plant spacing, improving water management during the early rice growth period, and efficiently using on-farm organic fertilizers over indiscriminate application of conventional fertilizers.

Export Quality versus Quantity

Vietnamese rice is exported in various qualities including 5, 10, 15, 25, and 100 percent broken kernels, glutinous, and jasmine. Vietnam’s growth technique has been to provide large quantities of low-grade rice to the global market. This strategy was born after a short lived hunger crisis causing the country to temporarily halt rice exports in 2008. The crisis was alleviated quickly by a large scale rice stockpiling program that prioritized quantity of rice produced over quality characteristics. As of 2016, the Vietnamese rice stocks were 9 million tonnes, 60 percent of which were food grade. Vietnam now has the reputation in global markets as a supplier of low-quality rice, which may hurt their chances of competing with countries like Thailand which produce rice perceived globally as being of higher quality.

Looking Forward

Competing strategies aimed at promoting growth cloud Vietnam’s rice outlook. The strategy of crop intensification competes with the ecological preservation of increasingly fragile rice lands. The push to produce more volume runs the risk of sacrificing rice quality and further damaging Vietnam’s rice export reputation. In addition to the market forces at play, the government continues to heavily subsidize national production of rice. Proponents of heavy governmental intervention in agricultural development applaud these measures as they support smallholder-led agricultural development. However, critics highlight that such heavy protection reduces a farmer’s ability to choose the best crops for their parcel of land, reducing farmer sovereignty and income potential. As Vietnam marches toward its next phase of development, rice export policy will be of high priority in a country caught between globalization and vestiges of protectionism.

Insight

InsightArgentina’s Wheat Exports to Shrink as La Niña Bites

Insight

InsightUSDA Cuts Corn and Soy Yield Projections, Moving Forecasts Closer to Gro's

Insight

InsightIndia Levies an Export Duty on Rice

Insight

Insight

Search

Search